Project Genius pyramid puzzle

Fri 26 February 2021 by Fritz Mueller[A catch-up article from Christmas, 2020]

My family knows I have a fondness for puzzles, so my son will typically gift me a few each year at Christmas. Among the puzzles received this year was the Project Genius Pyramid:

This is pretty entertaining to play with -- since the planes and angles are not orthogonal, the fits of the pieces are less familiar, and I found it more difficult than usual to use "geometry brain" to think ahead while exploring solutions.

I have recently been playing around a bit with Knuth's "Dancing Links" algorithm, described in his paper here. This is a relatively short paper, and if you are unfamiliar with it I'll say I feel it is really worth a read! The gist is a relatively straightforward backtracking algorithm for efficiently finding exact covers of binary matrices, packed with the usual Knuthian tricks and insights. As many classes of problems lend themselves to expression as an exact cover over a set of constraints, the algorithm has broad applications including tiling/packing problems (e.g. Pentominoes, Soma), general n-Queens, Sudoku, logic puzzles, etc. Having coded up an implementation (on Github here), it seemed it would be fun to extend it to explore the pyramid puzzle.

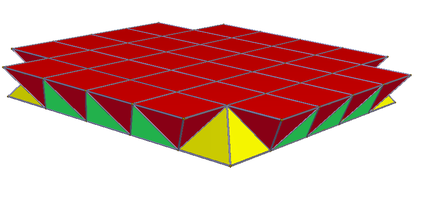

As a tiling puzzle, the first thing to understand was the cell geometry of the pieces and the space to be filled. The base geometry here is an alternated cubic honeycomb, composed of octahedra and tetrahedra. The complex in this case is further sliced into layers which bisect each octahedron, resulting in cells that are tetrahedra and upward- and downward- facing pyramids:

It turns out that the centers of these cells are arranged on a simple rectilinear lattice. The "flavor" (up-pyramid, down-pyramid, tetrahedron) of each cell is simply determined by its position in the lattice; for a cell at coordinates \(x, y, z\):

So, a simple three-dimensional array and indexing scheme may be used to represent the puzzle space, so long as sufficient care is taken with restricting possible piece placements to preserve flavor-invariance.

A further choice of the puzzle makers was to break a symmetry of the puzzle by choosing a layer height such that the cell-center lattice, while rectilinear, is not cubic (the octahedra in the fundamental complex are taller than they are wide/deep, and the tetrahedra are similarly stretched.) I am not sure whether this was done to avoid having the final pyramid look too squat, or if it was done deliberately to reduce the solution space. In any case, this means that we need only consider "right-side-up" and "upside-down" orientations of each piece; the potential "sideways" orientations do not fit the puzzle space.

A final consideration for the solver is restriction to essentially unique solutions by elimination of rotations, refections, and permutation of repeated pieces. This puzzle has some pieces that are chiral without reflected versions, and no repeated pieces otherwise, so reflected and permuted solutions do not exist. To account for rotations, I chose to restrict one piece ("E") to a single orientation (the "E" piece can only appear in solutions in its right-side-up configuration, because if placed upside-down it blocks any other piece form being able to occupy the apex of the pyramid).

These considerations were pretty straightforward to cast into code for the dancing-links solver; a subsequent run quickly produced an atlas of 80 essentially unique solutions. When physically replicating these with the puzzle, it takes a little practice to get used to moving from the rectilinear cell-center space in which the solutions are printed to the isomorphic pyramid/tetrahedron space in which the puzzle physically exists, but this becomes pretty easy once you've played around with it for a bit.

Of the 80 solutions found by the program, only one seems to be generally known on the web, which is the one published by the makers of the puzzle. It is solution 30 as found by the program:

#30: ┌───────────────┬───┐ │ A A A A │ B │ ├───────┬───────┤ │ ┌───────┬───┐ │ H H │ E E │ B │ │ I I │ E │ │ ┌───┤ │ │ ├───┐ ├───┤ ┌───┐ │ H │ G │ E E │ B │ │ G │ I │ F │ │ I │ ├───┤ ├───────┴───┤ │ ├───┘ │ └───┘ │ C │ G │ J J J │ │ G │ F F │ │ ├───┴───────┐ │ └───┴───────┘ │ C │ D D D │ J │ └───┴───────────┴───┘

For puzzle fans who may own this puzzle, here is an additional challenge based on some inspection of the atlas: some solutions found by the program have a contained sub-puzzle of a smaller pyramid with base 2x3 (in physical puzzle space, where the larger pyramid is considered to have base 3x3.) Can you find any?