Trav-ler 5028 Repair

Fri 26 February 2021 by Fritz Mueller[A catch-up article, documenting events of June/July/August 2020]

Something a little different this time! A friend of mine asked if I could help restore a late-40's portable AM radio set that had belonged to her grandmother:

I have done a lot of work with vintage tube instrument amplifiers, so familiar with many of the principles and challenges, but this would be my first radio. So quite a bit to learn!

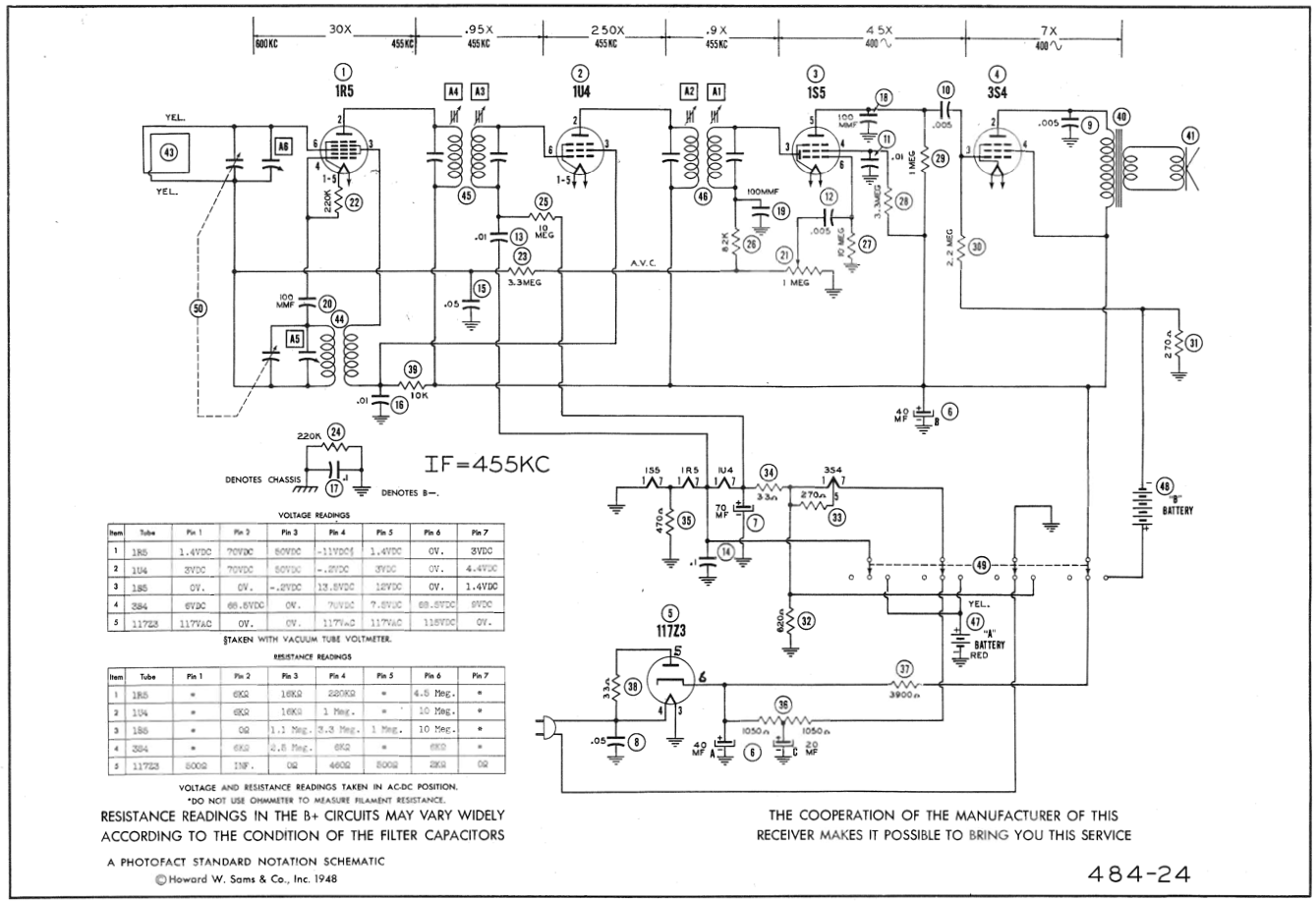

Researching this a little, here is the schematic:

It turns out that there were some very common designs for AM sets in this era, copied and tweaked slightly and produced by many different manufacturers. One cornerstone was the AA5 ("All-American 5"), a five tube superhet design. The tubes had their filaments wired in series, each dropping a bit of the input line voltage, so a power transformer was not required, reducing cost, weight, and size. The lack of a power transformer also lead to some of these radios having a "hot chassis" design, which was not without safety hazards -- more on this later...

There is much information available on the web concerning the theory and operation of the AA5 circuit, and a lot of restoration videos are also available. Interested parties are encouraged to Google, but for the purpose of exposition, I will summarize here in brief. Uninterested parties can scroll a few paragraphs past the indent to pick up the narrative :-)

Following circled numbers from the schematic above, one coil of transformer 44 and one half of ganged tunable capacitor 50 in parallel form a tunable resonant tank. Tube 1 provides gain, and the output is fed back positively via the second coil of transformer 44, forming a tunable oscillator. Antenna 43 and the other half of ganged tunable capacitor 50 in parallel also form a weakly selective tank, which picks up RF and dumps it onto an additional grid of tube 1. Tube 1 is arranged such that the a mix of the two signals (oscillator and weakly selected RF) appears at the plate.

The oscillator and RF thus mixed heterodyne against each other, forming frequency images in the output signal at both sum and difference frequencies; the difference frequencies will be of interest to us here. Since the frequencies in the weakly selected RF and the oscillator track each other, their differences are always centered on a fixed frequency, called the "intermediate frequency", or "IF". The remainder of the circuit need only be concerned with further selection, detection, and amplification at this fixed IF. In this set, the IF has been designed to be 455 KC (KHz).

Transformers 45 and 46, with their integrated capacitors, form cascaded selective bandpass filters at the IF. Tube 2 in-between provides gain and impedance matching between these stages. Tube 3 rectifies (negatively) the now highly selected IF carrier, and cap 18 drains away carrier signal components above the audio range, leaving just the amplitude envelope. Tube 4 provides a final power gain stage at audio frequencies, impedance matched through output transformer 40 to speaker 41.

One interesting refinement here is the "A.V.C." ("Automatic Volume Control"). This taps the detected audio signal and runs it through a long time-constant low pass RC filter, producing a slowly varying DC signal that tracks the audio volume. This is fed back as a bias to the tanks at the front end of the circuit, effectively "turning down" overly strong local stations, so they don't boom out of the radio inconveniently loud compared to more distant stations.

As a portable, this set could be operated off batteries as well as line voltage, but it required two types of batteries: an "A" battery, 1.5V, much like a modern "D" cell, and a "B" battery, 90V, long obsolete. I did not bother with battery support during the restoration.

A lot of the wiring in the radio had rubber insulation, which had hardened and begun to flake away. The wax-covered paper caps all certainly needed replacement, as probably did the multi-section cap in the power supply. One of the tube sockets, supporting a lot of the point-to-point wiring, was cracked and broken. The tuning dial string was broken. There were a few small tears in the speaker cone. Line cord insulation was brittle and broken, and the line cord itself was unpolarized. Rubber grommets holding the tuning capacitor had hardened and shrunk. Given all this, it seemed the best thing to do would be to break down the set completely to better be able to inspect, clean and make mechanical repairs. After this, the Hickock tube tester comes down off the shelf to check the tubes:

The 117Z3 rectifier was shot. Someone had substituted a 1T4 for the stock 1U4 in the IF interstage. And the 1R5 and 1S5 were weak. Ordered up some replacement tubes, caps, line cord, grommets, and a new tube socket.

Testing showed that the multi-stage power supply cap was indeed leaky, but I was not able to find a replacement of same dimensions (a 1" outside-diameter tube). I ended up making a replacement with a bit of model-rocketry body tubing, which I stuffed with some modern electrolytic caps of the appropriate values. The result can be seen in the middle picture below, where you can also see some speaker cone repairs done by brushing over the tears with a couple coats of thinned PVA glue. The last picture here shows the completed point-to-point rebuild:

A few words on hot-chassis design and safety: looking at the schematic above, you can see that there is no safety ground, an unpolarized plug, and one side of the AC line is connected through the power switch directly to the B- bus. This means if the line plug is put in one way, B- could be connected directly to AC hot when the radio is on; or if put in the other way, B- would be connected to AC hot when the radio is off, through the resistance of the tube filaments. On some radios slightly older than this, the B- bus is further connected directly to the radio chassis! That means you can get a nasty and dangerous shock off the chassis of such a radio, when the radio is either on or off, depending on which way you plugged in the plug. These radios depended on wooden or plastic cabinets and knobs to keep you from making direct contact with the chassis, but there were still often exposed bolts which connected to the chassis on the backs or bottoms of the cabinets. You were expected to know better...

This Trav-ler radio is a slightly later design, where the chassis is at least isolated from B- by a .1 MFD cap and 220K resistor in parallel. While you won't get such a nasty shock from the chassis of this radio, you can still get an uncomfortable and unsettling "tingle". And if that .1 MFD cap should fail short, your are straight back to danger-ville (on older instrument amplifiers, the capacitor in this particular role became known as the "death cap".)

An improvement for both situations is to replace the line cord with one with a polarized plug, and rewire the radio slightly to a) connect the now known-to-be-neutral side of the line directly to the B- bus, and b) move the power switch to interrupt the hot side of line. EMI filter caps (including the above mentioned "death cap") should be upgraded to modern X or Y safety caps, which are designed to fail open if they fail at all, so as to prevent fire or shock hazard.

Hot chassis designs also pose a challenge (and potential for some surprising moments) with your test equipment. You will often want "ground" for measurement purposes to be B- when working with these things. If this is at or near the hot side of the AC line, and your scope or test gear connects "ground" to safety ground (as most/many do), you are likely to explode the ground lead of your scope probe and/or damage the scope's input amps when you hook it up, with attendant arcs, smoke, and surprise... To reasonably work with hot-chassis designs, you must power them via an isolation transformer, so any point in the circuit under test can "float" relative to the ground of your test equipment. I strongly encourage people unfamiliar with this situation to research it on the web a bit before jumping in on servicing something like this for the first time.

Okay, back to the restoration... After hooking all this up, plugged it in and let it warm up, and while it did come to life and started pulling in AM (!) stations, it was far from optimal. Well, okay, so it needs an "alignment", which means adjusting the tracking on the oscillator and antenna circuits, and tweaking the IF selection transformers to peak up right at design IF. This is done on the bench with an RF test oscillator and a scope or analog meter (topic for another article!) After this, things were better, but there was still a lot of static when tuned in to stations, kind of a granular hiss. So, more research...

It turns out sets like this commonly suffer from something called "silver/mica disease". The IF transformers (45 and 46 on the schematic, the tall silver rectangular parts in the pictures) each have a pair of adjustable coils, and a pair of internally integrated capacitors. The caps in the transformers are typically made with a sheet of mica sputtered with sliver on each side, then sandwiched between a pair of contacts. Both capacitors within the transformer will typically share a single mica sheet substrate. In AA5-like circuits, one of these caps is operating at high potential relative to the other, and over time, dirt and grime provide a path that allows silver ions to migrate between the caps, eventually providing a bridge which rapidly arcs out. As this continues, the mica and silver plating are deteriorated and carbon deposits start to collect accelerating the process.

The cure for this is to open the transformers and remove the deteriorating mica capacitors, then add replacement caps either within the cans or beneath the chassis across the transformer legs. Below you can see some pictures of disassembly of one of the transformers, and the integrated capacitor contact legs at the bottom rolled back out of the way after the deteriorated mica sheet had been removed. Unfortunately, it seems I didn't catch a picture of the damaged mica itself, but a web search will show plenty of similar pictures:

The values of these deteriorated caps cannot be reliably measured, and their design values are not always marked on the schematics. Getting these right to the order of 10 pF or so is important; if they are too far off the available adjustment range of the ferrite slugs in the transformers will be insufficient to properly align the set. A handy approach here is to temporarily tack in some trimmer caps covering the appropriate range. The ferrite cores can then be set in the middle of their excursion, and the set aligned using the trimers; the trimmers are then removed and measured and fixed caps are selected to closely match their set values. An AC bridge is useful for accurate measurement in this range; here you can see a Fluke 710 which was salvaged from the lab:

After this final repair and another alignment, the set started to work quite well! I got lucky with timing and managed to pull in some era-appropriate material from Radio Yesteryear on KTRB while I was testing:

This was a really fun project, and I learned a lot along the way -- looking forward to doing a few more like this in the future!