PDP-11/45: Teardown and corrosion remediation

Sat 11 April 2015 by Fritz MuellerHad a little more time to work on the PDP-11 this weekend. Mostly going after some corrosion on the CPU cabinet and H742 power supplies. Tore these down, sanded down the corroded bits, then hit with a satin finish Rustoleum rattle-can which dries to a reasonable approximation of the original powder-coat.

Neon indicators on the H742s are dim and flickery, so ordered some replacements for these, too.

PDP-11/45: 861 AC power control

Sun 29 March 2015 by Fritz MuellerWell, might as well start at the beginning with the AC power system, so here's the 861 power control. In very good shape for some 40 year old kit! The neon indicator lamps have gone, so I sourced the modern equivalent and put them on order. Everything else is tight and clean:

PDP-11/45: Begin Again

Sun 15 March 2015 by Fritz MuellerBack in the mid/late '80s, when I was a student at CMU, a computer club member introduced me to the club's nearly forgotten hardware lab. It was still stuffed with remnants of the earlier time-sharing age, including two or three full-cabinet PDP-11 systems with names like "Banshee" and "Centaur". I thought these were the coolest -- CPUs you could see inside, and hack with a soldering iron and a wire wrap gun. Real front panels with lights and toggles, and machine language programming as a physical activity. For a kid fascinated with computers, it was great. You couldn't get closer to the metal; you could quite literally get your head inside these machines.

I began spending off hours in the lab, puttering with the '11s and getting to know them. Eventually, the club decided it was time to clean house and remove all of the older equipment. Most stuff was scheduled to be hauled away to the dump, but I was welcome to anything I wanted to haul away myself in advance. So I bothered some friends with a car, disassembled one of the '11/45s there ("Banshee" I believe) which seemed like the nicest thing, and hauled it off to my off-campus house. There it resided in the basement with many other oddments for some years.

Eventually, I ended up moving out to CA, and after some time the 11/45 CPU was disassembled and packed into moving boxes for the west coast as practically as possible, leaving all the bulkier parts behind.

After a couple of years in CA, I happened on a decommissioned two-rack 11/40 system at Stanford, essentially free for the effort of hauling. This had most of the missing cabinetry, power supplies, and peripherals needed to reconstruct the 11/45! So I procured this and added it to a growing west coast equipment stash. And then real-life set in -- job changes, house moves, raising a kid... Through all of that I held on to all the parts, vowing to "get to it someday". I would pick through the stuff from time to time over the years, but never had the time to take the project very far.

Well, now "someday" is here! The kid is off to college and I've moved house once again, but this time I reserved some working space for the project and pulled all the parts so they are together and accessible. So here we go...

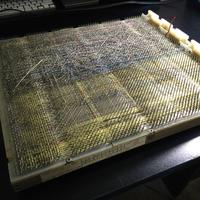

Here are some pics from the first weekend: the two H960 racks that are the bones of the whole thing, some glamor shots of the processor backplane and the RK11-C disk controller, and my buddy Chris helping to remount the RK05 drives on their rails temporarily to keep them off the floor and out of harm's way:

three.js and JSFiddle

Tue 02 December 2014 by Fritz MuellerHere's a small web toy, as a test of embedding a client-side visualisation in this blog. The toy written in JavaScript using the Three.js 3D graphics library, and is hosted at JSFiddle.net. If you click the "Edit in JSFiddle" link, you'll go off site to a full multi-pane view of the toy, where you can inspect and modify and play with the various parts of the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript.

Moebious transformation animated GIFs

Mon 01 December 2014 by Fritz MuellerHere are some animated GIFs that I created a few years ago with MATLAB. These characterize the action of the four classes of Moebius transformations, mapping the complex plane to itself. They were inspired by the illustrations and analysis in a section of Tristan Needham's excellent book Visual Complex Analysis:

So what's it all about? A Moebius transformation is a mapping on the complex numbers of the form

where \(a, b, c, d\) are complex constants. Moebius tranformations have many nice features: they are one-to-one and onto on the complex plane (extended with the addition of the "point at \(\infty\)"), they form a group under composition, they are conformal (angle preserving). Interestingly, though conformality only implies that they map infinitesimal circles to other infinitesimal circles, Moebius transformations actually map circles of any size in the complex plane to other circles in the plane. For a really nice exposition and proofs of these qualities, see Needham.

Fixed points on the plane under a Moebius transform will simply be solutions of

which is just quadratic in \(z\). So a (non-identity) Moebius transform will have at most two fixed points, or one when there is a repeated root. Following Needham, for the remainder of this discussion we'll refer to the fixed points of a given Moebius transformation as \(\xi_+\), \(\xi_-\) in the two root case, or just \(\xi\) in the repeated root case.

Most of the qualities above are readily observable in the animations: one or two fixed points, circles mapping to circles, one-to-one, easy to imagine extension to the whole plane. Conformality is a little harder to see, but if you look closely you can see that the angles at each of the corners in these crazed checkerboards always remain 90°.

The GIFs were generated using a transform method. Given a Moebius transformation with two fixed points (we will revisit the single fixed point case shortly), consider the additional Moebius transformation defined by

This will send \(\xi_+\) to \(0\), and \(\xi_-\) to \(\infty\). We can now construct

which is itself a Moebius transformation (since the Moebius transformations are a group under composition) and which will have fixed points at \(0\) and \(\infty\). We can consider \(M\) and \(\widetilde{M}\) to be a transform pair; for any \(M\) there is a corresponding \(\widetilde{M}\) with fixed points at \(0\) and \(\infty\).

Now it turns out that Moebius transformations with fixed points at both \(0\) and \(\infty\) reduce to a particularly simple form — that of a single complex multiplication, i.e. just a dilation and/or rotation about the origin of the complex plane. See Needham for exposition of this. The elliptic, hyperbolic, and loxodromic classes of Moebius transformations turn out to be those whose corresponding \(\widetilde{M}\) is a pure rotation, pure dilation, or general combination of the two, respectively.

To generate these GIFs, we decorate the complex plane on the \(\widetilde{M}\) side like a circular checkerboard or dart board, and represent the action of a given class of \(\widetilde{M}\) transformations by rotating it, dilating it, or a combination of both, e.g.:

On the \(M\) side, we can pick fixed points \(\xi_+\), \(\xi_-\) wherever we like, and then derive the corresponding \(F\) as above. For each frame, we take each point on the \(M\) side, map it through \(F\) to find the corresponding point on the \(\widetilde{M}\) side, and check that against a dynamic checkerboard model to see if the point should be black or white in this frame.

Returning to the repeated root, single fixed point case: we treat this similarly, but set

which sends \(\xi\) to \(\infty\). As before, it turns out that Moebius transformations of this form (repeated fixed point at \(\infty\)) reduce to a very simple form: this time, a pure translation. The parabolic class of Moebius transformations are those whose corresponding \(\widetilde{M}\) transformation is a pure translation. To illustrate these, we use a translating dynamic checkerboard on the \(\widetilde{M}\) side that looks like this:

All of this can be done quite succinctly in MATLAB, once it is understood what needs to be done. Below is the MATLAB snippet which was used to generate these GIFs. Commenting and uncommenting various lines chooses different \(F\) and \(\widetilde{M}\) side checkerboard models, resulting in the different outputs.

The first few lines create a 512x512 matrix of complex numbers, ranging from -3 to 3 on both the real and imaginary axes, to represent a portion of the complex plane. This is then pre-mapped through an appropriate \(F\). The for loop iterates on each frame. The dynamic checkerboard result is calculated as the xor of various versions of functions g1 and g2 operating over the premapped points. Each frame is downsampled and written to disk as a separate file, then at the end all the frames are stitched into a movie. I must then have used some non-matlab utility to convert the movies to animated GIFs, but I'm not sure what that was...

Z = -3:6/512:3-(6/512); Z = Z(ones(1,length(Z)),:); Z = complex(Z,Z');

%Z = 1 ./ Z; % one finite fixed point

Z = (Z+1)./(Z-1); % two finite fixed points

im = []; g1 = []; g2 = [];

for frame = 1:30

g1 = mod(log(abs(Z))*4,2)<1; % radial, static

% g1 = mod(log(abs(Z))*4+(frame-1)/15,2)<1; % radial, dynamic

% g1 = mod(real(Z)+(frame-1)*.8/30,.8)<.4; % vertical, dynamic

% g2 = mod(angle(Z), pi/6)<(pi/12); % circumferential, static

g2 = mod(angle(Z)+(frame-1)*pi/180, pi/6)<(pi/12); % circumferential, dynamic

% g2 = mod(imag(Z),.8)<.4; % horizontal, static

im(:,:,1,frame) = imresize(xor(g1,g2), .25, 'bilinear');

imwrite(im(:,:,1,frame), sprintf('frame%.2d.bmp', frame));

end

mov = immovie(255*im,gray(255));

movie(mov,50);